In the fourth session of the seminar course we look at the last of our teachers in this project, Deleuze and Guattari (mainly Guattari to be honest). The notes for the session are below the video.

TFS Session 4

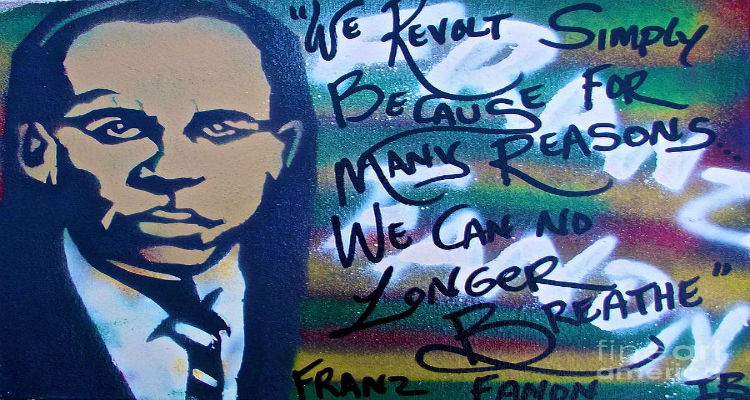

In many ways the project is best understood as being located within schizoanalysis, in fact, the self-description we offer is that we’re thinking a Fanonian Schizoanalysis, one where the wretched of the earth are thought entwined with the wretched earth, one where the voices of the revolutionary in Fanon or Guattari are in chorus, resonant and vibrant. There is still the question that has been raised, of what difference does this make. What difference does thinking make, particularly when the mode of thinking is one in which the rational intellect is no longer master. Part of the answer comes from the idea of abstract machines.

In the first chapter of Guattari’s Chaosmosis – an ethico-aesthetic paradigm, it’s made clear that the idea of an abstract machine derives from a “brilliant intuition” from the linguist Hjelmslev (p23). It’s also clear that the role of the abstract machine as found in linguistics is to be expanded, pushed out beyond the domain of language into the “extra-linguistic, non-human, biological, technological, aesthetic, etc” (p24). Guattari continues:

The problem of the enunciative assemblage would then no longer be specific to a semiotic register but would traverse an ensemble of heterogeneous expressive materials. Thus a transversality between enunciative substances which can be, on one hand, linguistic, but on the other, of a machinic order, developing from ‘non-semiotically formed matter’, to use another of Hjelmslevs expressions.

These couple of sentences immediately drop us into the strange world of Guattari’s schizoanalytic cartographies, where there is this intense jargon or complexity, where amidst a swirl of concepts, connections and strange words, a strange dynamic can be sensed, one in which the world itself speaks, or something like that.

Let’s just work through this passage. ‘The problem of the enunciative assemblage’ – let’s begin there. To enunciate, to speak well, to enunciate your words.

Think here of the way an accent is so often a component of speech. Or think of the mouth, its formation and function, the throat, the lungs, the diaphragm. Breath and breathing. Rhythm, connotation, association. Or power, a judge handing down a sentence, a word within a specific frame of power – “Detention!” shouts the teacher. Or the famous example of someone shouting “Fire!” – it makes a difference when it’s in a crowded cinema, or perhaps when it’s on a firing line, as the enemy approaches.

The ‘problem of the enunciative assemblage’ is basically the problem of how that which speaks is able to do what it does. The functioning of the enunciative assemblage – how it learns to do what it does, how the functions ‘operate’ in practice, how we work out what ‘minor components’ make up the ‘major assemblage’. All these questions, and more, form ‘the problem of the enunciative assemblage’.

Within Guattari’s account in the first chapter of Chaosmosis, he’s specifically looking at the relation between subject and object, very traditional philosophical territory in many ways, so in large measure, the problem of the enunciative assemblage is approached via the ways in which the relation of an object to a subject develop. This is also where we find Guattari’s emphasis on ‘the productions of subjectivity’ and it can be easy to slip back into the human a little too quickly at this point. So, a word of caution – the schizoanalytic framework takes language to be only one situation within a wider context of non-linguistic enunciative assemblages.

Guattari again, slightly earlier in the passage just cited:

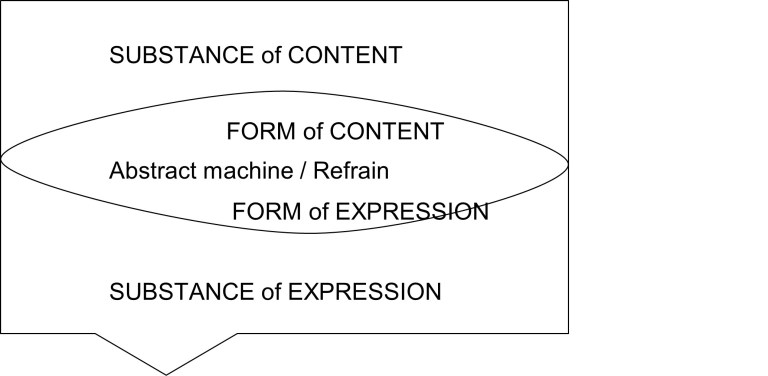

“…we would like to resituate semiology within the scope of an expanded, machinic conception which would free us from a simple linguistic opposition between Expression / Content, and allow us to integrate into enunciative assemblages an indefinite number of substances of Expression, such as biological codings or organisational forms belonging to the socius.” (ibid)

Notice the way that the desire in this passage is to be ‘freed up’, via the concept of machines, the ‘machinic conception’. The strategic argument here arises from the aim of ‘freeing’ a way of understanding language from a ‘simple linguistic opposition’.

Why and How? These two issues are distinct, but the abstract machine is part of the How…

Before we get onto more details of this ‘how’, we should first pay attention to the ‘why’.

Here the guiding question is something like, who is speaking? The way in which this question should be heard is important, however. It should be contrasted, or at least thought in tension with, the question ‘what is speaking’?

‘What is speaking’, for example, might enable us to see that there are other forces at work in expression – forces such as the unconscious, or forces such as the racialised value system of colonialism. For example, might we say that in Fanon, what is speaking in ‘the black mans experience’, as he describes it in Black Skin, White Masks, is both racism, in other words the value system of racism, in which the black man is inferior and the resistance to that value system that expresses something named as human. Two different drives or dynamics in tension.

But who is speaking? This is Fanon himself. Not some structure, not some training, nor even some biography, but nonetheless Fanon is who speaks here. Or part of Fanon, at the very least.

Who is speaking?

There’s a key formula that can be found all over the place when it comes to psychoanalysis, and it goes something like this: the subject of psychoanalysis is the subject of transference.

Let’s think, for a moment, about that analytical model of the unconscious drive. There is, in Freud, a basic tension between id and ego that I described last week as a kind of ‘domestication’ model. Unruly, free energy is organised into a coherency over time by its relations with the self-conscious ego. This is a kind of self-organising process, no strict architect at hand, rather a set of major factors and their interactions. Id, ego, pleasure, sociality. Self-organisation takes place, subjects form personalities if you like, but within a system of effectively pre-established factors. We assume certain things, the free energy of the id for example, or the restrictive nature of the social, and then work out our ‘causal narrative’ from these factors. Accidental factors, trauma for example, impact as something like ‘external forces’ and so we have quite a rich set of characters to form a story with. The idiosyncrasies of the individual can be accommodated as ‘tones’ or ‘colours’ within a basic plotline. Yet the plotline has to be assumed. The story is already told, just not the details of the moments.

So in the process of analysis, what is speaking is less the details, the manifest content that we encounter in the words, actions, emotions of an individual, more the plot point of the story itself, the latent content. Transference is the process by which the conversation in the analysis is recognised as expressing not just the people sitting in the room but the characters that accompany the individuals. The past. The story so far. Transference is the moment when the refrain from another character is expressed in the words or actions of the therapist. In more Jungian language we might find the sense of projection and archetype, and there’s a sense in which transference and projection are trying to think something similar. Often these ‘transferential relations’ are encountered through feeling – “I feel like this is what my mother says”.

What speaks, then? What speaks, for psychoanalysis, is the past, the way body and thought connected, the way a word or object was felt. The past over-codes the present and future. What speaks is the past, not the future.

How would we even be able to hear the future?

Perhaps this speaks to the ‘why’ of the abstract machine.

The abstract machine is the core of an assemblage, its nuclei. Guattari often compares abstract machines with Universals, or with Abstractions. Yet the comparison is disjunctive, one of comparison and distinction. The abstract machine is different from the Universal or the Abstraction in that it offers an open, rather than a closed, form of consistency.

This is no doubt an odd phrase, a form of consistency, but for now let’s just think of this in terms of something like ‘that which enables us to take an object as an object’. Out of the various different elements and moments that make up a tree, for example, there is some kind of consistency that brings them together as the tree, like this tree. This binding together, this is a coming to consistency, a coming together or a being taken together. If we’re thinking of trees, or tables (famously), we might talk about an Idea or Form or even a Concept of the tree, some abstraction that operates as a way of bringing together various specific things.

Now, the abstraction or Universal has been a long-standing strategy in philosophy to understand difference and diversity alongside sameness and unity. Traditionally we have those who think such things as Universals exist and those who think that they don’t and that it’s all in a name, one of the reasons the opponents of Universals are called Nominalists. The disagreement is around the question of whether Universals exist or not. Are they needed? Are they, as it were, “out there”? For the Universalist, the problem is one of explaining where this “out there” is. They can explain how we bind things together, making a unity out of diversity with abstraction, but they have to assume something like a special realm of Universals – and mostly they don’t want to go fully Platonist and declare that there’s a realm of Forms, eternal and shining bright. On the other hand the Nominalist doesn’t need a special realm of abstractions that we have access to, they can rest on the fact that we just happen to call some things by the same name. The problem then is that these names are pretty arbitrarily applied. We’ve no real grounds other than habit for thinking that there’s a consistency between various things we think of as trees. In both cases, however, there’s an inbuilt passivity here. We either recognise universals that already exist or we submit to habits of naming things, habits that already exist. The past dominates the present. The form of consistency is thus a mode of passivity.

This is the why of the abstract machine – to produce an open form of consistency as opposed to a closed form.

One of the reasons for this openness is that the abstract machine organises the past as much as the future. This means that something like retroactive causation is being suggested, but that brings with it a whole bunch of problems. Let’s avoid this for the time being. Instead, let’s look a little at the ‘how’ of the abstract machine.

If the ‘why’ is that we have an open form of consistency rather than a closed (and we might want to explore in more details why we want an open form of consistency) then the ‘how’ is that the abstract machine produces consistency without causality and it does so, in part, because causality arises from consistency.

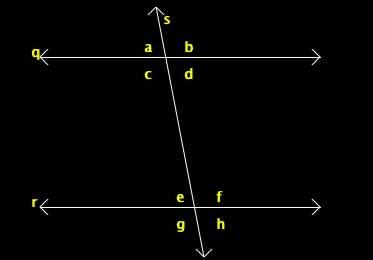

Consistency arises from a binding together of forms. This why Guattari was so fascinated, I think, with the way Hjelmslev had his four concepts – expression/content and substance/form. It meant that, at some point, there was a common formal moment that could be posed as the moment of constitutive consistency of both a form of content and a form of expression that produced substances (substances of expression and substances of content). This common productive space of forms – or rather of consistencies – is what’s also embraced in Freud in terms of desire and in Marx in terms of labour.

The ‘double articulation’ that is the focus of this chapter is that of the ‘codes’ and ‘territories’ that are probably quite familiar to readers of D&G. The processes of code and territory produce many of those curious ‘jargon’ terms so hated by critics, terms like decoding, overcoding, surplus value of code, deterritorialization, reterritorialization. At heart, these two processes, of code and territory, involve processes and because of this the dynamics of those processes, whether they are opening or closing dynamics, are central to D&G’s discussions. What purpose do these processes have in the analytical model of schizoanalysis? They are replacements or alternatives for more traditional philosophical concepts of ‘form’ and ‘content’ and are intended, I think, to transform the analytical categories that are used to understand specific ‘objects’ (concepts) of discussion. So, when talking, for example, about the ‘nature of subjectivity’, we could analyse it in terms of codes and territories rather than in terms of language, experience, ideology, genealogy or substance. We might presumably do something similar for concepts such as ‘nation’, ‘class’, ‘freedom’ or ‘truth’.

The ‘double articulation’ that is the focus of this chapter is that of the ‘codes’ and ‘territories’ that are probably quite familiar to readers of D&G. The processes of code and territory produce many of those curious ‘jargon’ terms so hated by critics, terms like decoding, overcoding, surplus value of code, deterritorialization, reterritorialization. At heart, these two processes, of code and territory, involve processes and because of this the dynamics of those processes, whether they are opening or closing dynamics, are central to D&G’s discussions. What purpose do these processes have in the analytical model of schizoanalysis? They are replacements or alternatives for more traditional philosophical concepts of ‘form’ and ‘content’ and are intended, I think, to transform the analytical categories that are used to understand specific ‘objects’ (concepts) of discussion. So, when talking, for example, about the ‘nature of subjectivity’, we could analyse it in terms of codes and territories rather than in terms of language, experience, ideology, genealogy or substance. We might presumably do something similar for concepts such as ‘nation’, ‘class’, ‘freedom’ or ‘truth’.