Category: flow

-

As an introduction to schizo-analysis: responding to ‘The Anti-Oedipus Papers’ (unfinished notes)

(First published Jan 1st 2007, minor edits made. Republishing Oct 3rd 2019, as I start my second run of the course ‘Schizoanalysis for Beginners’).

There is a background to every text, a life, a thought, an obsession, a spilt cup of coffee on papers badly placed on a temporary desk. Good sex, drunken rants, flirtatious concepts, all of these form part of that which will never be said within the text, only ever sensed, occasionally and differently, by the readers and writers who follow the words along the page. This, maybe, is why people want to read biography, interviews, trivial detritus from the lifetimes of another, the writer, the author, the proper name appended to the title. When the text is one within philosophy there’s this sense that somehow knowing about the brandishing of a poker or the peculiar arrangement of garters, socks and toilet habits, somehow knowing this will help know the concepts. This betrays a latent humanism, most often, where we want to know what the author thinks, we want to discern accurately, so we think, the moments that occurred in someone elses’ mind and re-occur them in our own. There seems no reason to assume this humanistic notion of a transport of ideas from one mind to another as the central task of reading and interpreting a text. There seem many reasons to assume that a text is in fact nothing to do with an author to the extent that the act of reading occurs without any author and if the text works it works without an author other than the reader. Would it matter, say, that the images and ideas drawn from a book that had been read under one name suddenly found themselves shifted to another name? It might matter in terms of understanding the author but surely the point of reading is to understand the ideas and images not the author? Otherwise I would always be in a better position to understand an author by talking directly to them and not reading their work? The author really does seem somehow redundant, theoretically, since it is the ideas and images that we are interested by and in.

Despite this, those texts that occur on the margins of ‘real’ texts, authorised works, always seem to have a strange, uncanny necessity to them. This is no less the case than in ‘The Anti-Oedipus Papers’ by Felix Guattari, a collection of strange and varied notes and jottings produced in the course of writing, jointly with Deleuze, the work ‘Anti-Oedipus’, the first volume of ‘Capitalism and Schizophrenia’. When I first acquired this text a few months ago I read through it quickly and briefly, finding it strange and impenetrable, dismissing it as a rather weak and perhaps idiotic collection put together more as part of an attempt at hagiographical recuperation than intelligent concept creation. Guattari is increasingly viewed as an aberrant force on Deleuze, the ‘wild’ infecting the ‘pure’, lunacy implicating itself into rigour. Zizek is no doubt the main location of such a view (in his ‘Organs without Bodies’) but it’s not isolated to him alone and the increasing interest in the central and more ‘classically philosophical’ work such as ‘Difference and Repetition’ also appears at times, justifiably or not, as the result of an attempt to subtly, perhaps even subconsciously, purge Deleuze of Guattari. In this context ‘The Anti-Oedipus Papers’ (henceforth AOP) might be thought as an attempt to regain the crucial duality or pluralistic-monism of the name ‘Deleuze-Guattari’. All this, however, would be to miss the point or purpose of the AOP. There is no hagiography here, nor any attempt to somehow provide evidence for the absolute necessity of the double name. Instead there is a kind of compassion.

The AOP is first of all material. There is an introductory essay but I will ignore that, as though it doesn’t exist, since the papers themselves need to live. This time I decided to re-read the text during the xmas holiday break. I had picked the book up again a few weeks ago and for a while it sat, barely touched, on the bedside table where an ever shifting pile of texts moves through the dream-world of evening reading. These texts are usually chosen through a kind of intuition, something hinting at their interest, some curious phrase, name, image or event suggesting that, for some reason not yet clear, they will be of interest. Commonly this is the place for poetry and novels, my work-desk covered in philosophy texts, administrative bureaucracy and the portals to technological otherspace (internet, psp, mobilephone, digital camera). The bedside table texts slip inside the peripheral boundaries of reason, occasionally exploding into an event, text, lecture or image. They are the necessary distractions, the differential grenades.

As I skimmed across AOP this time I came across the odd phrases, lines and words that seemed incomprehensible and instead of dismissing this as something for which I had no time instead felt comfortable in a language of sense beyond sense. It was clear as I read that there was this enormous production of words and the further I read the more I returned to my time of reading Artaud. That was a time, during the writing of my doctoral thesis, that lasted about 6 months, when all I did was read words of Artaud, about Artaud and with Artaud. It produced almost nothing of use in the thesis, no chapter, no ‘theses’, no critiques or necessities or tools or arguments or images but instead it provided a massive affect of wonder, joy, sadness and life. Resonance. There is no reason for resonance, though it may be analysed and its genealogy traced. The production of resonance, however, is a moment of beauty in the encounter, the moment when something contracts and forms itself as a crystal of thought to be taken and warmed during the course of the following times. A quote, a phrase, an image, these are usually the tokens of such resonance, tokens that we then exchange in the snake-oil discourse that surrounds and constructs our sociality. The resonance itself is, at its purest, something that cannot be contracted, something that resists being repeated through tokens and calls, instead, for a loyalty or trust, a kind of honouring of its existence. This is the case with Artaud and it is no surprise that the doorway into Artaud led through the Deleuzian phrase ‘bodies without organs’, which I took as a token of the ‘Artaud-encounter’ and which proved no mere token but rather an introduction, in the sense in which Heidegger introduces us to metaphysics. AOP, in this sense, produced a resonance, a kind of material space of encounter in which Anti-Oedipus is introduced as no mere text but as a production of newsense, an introduction to schizo-analysis.

I am not writing a review then. A response perhaps. Last night, for example, as I sat with a friend of mine whose currently training in clinical psychology having completed his MPhil in philosophy a few years ago, we were discussing the practicalities of schizo-analysis. There is, I said to him, something that must be irresponsible in schizo-analysis. The analyst must act responsibly to achieve the state of power that constitutes ‘being an analyst’ but from them on, if they are to engage in schizo-analysis (and if they don’t then they essentially fall into the power relation they’re constituted by, with its attendant inevitability of having ‘power-over’) they must allow the irresponsible in, for this is the condition of experimentation without theory, the condition of being able to analyse without the oppression of the imposed theoretical construct enforcing a rigid and static meaning on the analysand, converting, at that point, the therapist as the rapist. To break theory, the flow of theory, and intersect instead with the actual, with the presented as presented flow, requires some irresponsibility. There is no way of being accountable for the break with theory, there lies within it a kind of megalomaniacal belief. This, I said, was found in the repetitive trope of ‘fuck it’ found in AOP, the way Guattari releases a frustration through this language. Fuck it, fucking hell, what a fucker. It’s akin to the exclamation mark, the mark of passion, another frequently used mark or word in AOP.

Then there’s this sense of Guattari struggling with words – words, words, more fucking words. The same thing that animates any writer, something that occurs in the nomination of oneself as writer, that desperation, the fact that, as Deleuze says somewhere, we only write about that which we don’t know. I write and then I read what’s written and try to understand why I wrote that, how I wrote that, who wrote that because it wasn’t me. As the project nears its formal completion and ‘Anti-Oedipus’ is finished Guattari cries that he will be held to account, people will ask questions, he will be thought to be, somehow, responsible for the words and that he has tried hard to avoid this previously. Before ‘Anti-Oedipus’, he wails, he was able to walk away, turn his back and say nothing, say something else, explode irresponsibly as a flow, rather than an in-dividual, as an endpoint to flow.

There’s this strange relation to analytic theory as well. Guattari take liquid ecstasy and tells his partner that he wants to fuck around. His molecularisation concepts impinge themselves and he holds to the delirium of the drug as a truth, somehow revealing the real Guattari, the liberated flow, when as we all know, the drugs flow, not you. That which is said on drugs is nothing other than the drugs. There is no ‘real flow’ unblocked by the chemical, just another flow which we’ll be attached to through a kind of family resemblance or filial link. “It came from mymouth thus it’s affiliated with everything else that comes from mymouth”. The reality, of course, is that a thousand angels speak through mymouth, the hiss and buzz of the goetic hordes, the insectoid machines of signification bubbling over desires incarnated in chemical interactions.

The same imposition of theory onto flow occurs as he analyses his relations to fanny and gilles, the former who he wants to fuck, and the latter whom he seems to conceive as someone he must want to fuck even though such a desire is inapparent, hence, obviously, repressed. Fucking is taken as somehow meaningful in itself, as revealing something, other than the chimplike movement of bloodflow, hormonal interaction and a remarkably sophisticated antenna for opportunity. Everyone would fuck everything if they had the opportunity. The interesting thing is not why they do, but why they don’t. The break is the point of creation in the fuckflow. Guattari appears in these texts as classically heterosexual, for whom opportunity is inscribed in woman and not man and yet whose theories tell him such inscription is after the fact, that desire is genderfree, polymorphic. If the fuckflow is polymorphic, the breaks reveal the creation of something, indeed, but not necessarily a repression – it may as likely be a compression. That the opportunity is inscribed in woman more than man for the male heterosexual is no different, no more repressive, then if the fuckflow is inscribed predominantly in the same sex. It’s simply an asymetry. Nothing more. Where is the repression? Nowhere other than the theory, deriving its values from pre-theory, from a systemic asymetry that is no longer part of the fuckflow but which predominantly presents powerflow.

My response to AOP then is a reponse to a text that is not intended simply as the presentation of ideas, content separable from the presentation, but like poetry or novels, contains a production that is entwined in its presentation. It’s the material for a schizo-analytical re-reading of ‘Anti-Oedipus’ and schizo-analysis itself, the non-existent form of analysis, the peripheral possibility of revolution rejected by the analytic community almost everywhere. As such, perhaps, it offers once again the glimmer of the possibility of revolution in the practical work of desirefuckedup that is the condition of possibility for analyses as a practice. This glimmer can be named; compassion.

-

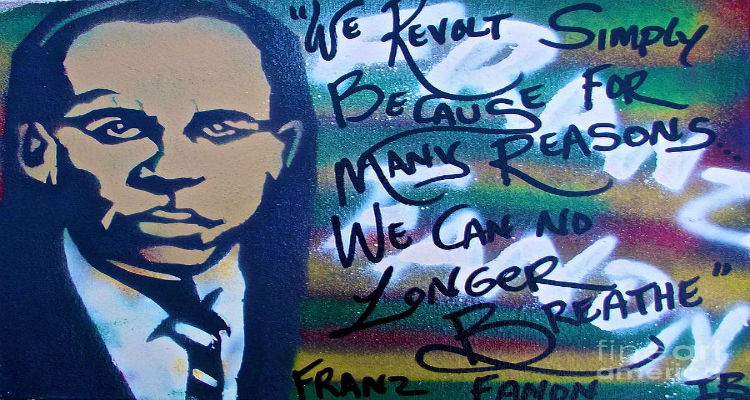

Making a body that questions

There’s been a little flurry of activity, with regards papers and the like, over the last month or so and the last part of that flurry was a lecture and workshop on the work of Fanon, held at Goldsmiths University on 13th November. Eric Harper, with whom I’m writing a book, co-presented and the session consisted of a short lecture by Eric and then me, followed by an hour and half workshop. I will post some reflections on the session at a later date, hopefully later this week, but for now here’s the notes I used as the basis of my lecture, mainly made available because I said I would do so for the participants. As with most lecture notes, I expect they are slightly fragmentary for anyone who wasn’t at the session.

There’s been a little flurry of activity, with regards papers and the like, over the last month or so and the last part of that flurry was a lecture and workshop on the work of Fanon, held at Goldsmiths University on 13th November. Eric Harper, with whom I’m writing a book, co-presented and the session consisted of a short lecture by Eric and then me, followed by an hour and half workshop. I will post some reflections on the session at a later date, hopefully later this week, but for now here’s the notes I used as the basis of my lecture, mainly made available because I said I would do so for the participants. As with most lecture notes, I expect they are slightly fragmentary for anyone who wasn’t at the session. -

City psychosis.

The twentieth century witnessed the rapid urbanization of the world’s population. The global proportion of urban population increased from a mere 13 per cent in 1900 to 29 per cent in 1950 and, according to the 2005 Revision of World Urbanization Prospects, reached 49 per cent in 2005. Since the world is projected to continue to urbanize, 60 per cent of the global population is expected to live in cities by 2030. The rising numbers of urban dwellers give the best indication of the scale of these unprecedented trends: the urban population increased from 220 million in 1900 to 732 million in 1950, and is estimated to have reached 3.2 billion in 2005, thus more than quadrupling since 1950. According to the latest United Nations population projections, 4.9 billion people are expected to be urban dwellers in 2030. – Source: World Urbanization Prospects: the 2005 Revision

Inspired by a reading of Lewis Mumford’s ‘The city in history’ I’m currently beginning a slow process of thinking about the role of the City in the human ecology. I turned to Mumford because of the scattered references to his work in Deleuze and Guattari’s ‘Capitalism and Schizophrenia’ project, and that has already proved productive, not least because of the realization that the ‘paranoid/schizoid’ poles that run throughout that project seem to have some roots in Mumford that I had not registered before. In Chapter Two, for example, Mumford develops his idea of the City as an ‘implosion’ event in human culture that arises from a dynamic between neolithic ‘villages’ and paleolithic ‘hunters’ which gradually produces the role of Kingship, the catalyst for the implosion event of the City. With this implosion event, dominated by a central authority, a new “collective personality structure” (p.60) develops. The idea that this new collective personality structure is one that connects a paranoid to a schizoid position is clear, for example, in the following:

Not merely did the walled city give a permanent collective structure to the paranoid claims and delusions of kingship, augmenting suspicion, hostility, non-cooperation, but the division of labour and castes, pushed to the extreme, normalized schizophrenia; while the compulsive repetitious labour imposed on a large part of the urban population under slavery, reproduced the structure of a compulsion neurosis. (p59-60)

Mumford is enjoyable to read, so far at least, because of his richly interpretative and evocative approach. He develops a very broad synthesis of ideas and histories in order to tell something like an ‘origin myth’ and this is both the strength and weakness of his book so far. At times he seems to be simply telling a story, at other times attempting to synthesise existing knowledge, always hovering on the edge of actually showing anything to be the case, instead maintaining this suggestive dynamic, hence why it seems akin to an ‘origin myth’ that is being presented. That said, this is only the initial impression from the first couple of chapters of the work and is something that I hope changes as I work through his large text. It would be disappointing to find that ‘origin myth’ style continues for all 650 or so pages, which I doubt it does, but it’s still interesting to encounter it.

Reading Mumford prompted me to look at some of the data regarding urbanization and some very limited research brought up the recent ‘transition point’ shift taht made the news around about 2006. The shift from rural to urban world population crossed the 50% urban population mark in 2006-2007 and is still climbing. Using data from the World Bank, as presented by Google, this shift can be seen in the following:

(UPDATE: missing graph it was here once but got lost in server migrations at some point and reconstructing it now would be a right pita, ML 2022)

Although a more interesting graph is the one that represents this growth in terms of regions, as follows:

(UPDATE: again, missing graph it was here once but got lost in server migrations at some point andreconstructing it now would be a right pita, ML 2022)

In the regionally differentiated graph it’s clear that all areas of the world are subject to the same basic direction of urbanisation, although unsurprisingly it is North America that has the highest ratio of urbanised population.

Now graphs are terrible things in many ways, delusion engines of the highest degree if taken uncritically, and so I’m not exactly sure quite what these graphs show and wouldn’t want to make any claims about what’s really going on behind these data sets. However, graphs derive their delusionary capacities from their ability to present ‘seemings’, that is, to show how something seems to be operating. Given this rather large caveat, one of the things that seems to be shown in these graphs is that there is a rather uniform and reasonably drastic increase in urbanisation between the years of 1960 and 2012. It also seems that the data within this particular window is a little odd. I haven’t been able to find an easy source for data that goes back, say, to 1860, let alone 1760 or even earlier but one of the things that seems rather obvious is that whatever the function that is operational within the 1960-2012 framework, it must be a different function from that which was operating, for example, between 1760 and 1960 and that seems to be the case for one very simple reason. If we were to take the left hand side of the graph and simply push the numbers down to zero on the basis on some sort of pattern available from the snapshot in the graphs (Rational Health Warning, see footnote *1), it would seem that such a ‘zero urban population point’ would occur around about 1850. That seems a little odd, not least because the City is a function of human life for far longer than the last 170 years. In fact it might reasonably be thought that the City has been one of the central, perhaps even the most central, feature of human life for anywhere between the last two to four thousand years (cf. Mumford). Of course, ‘urbanization’ and the ratio of the urban to rural population is a different phenomena from ‘the City’ so it might be wrong to conflate the two and in addition the ‘1850’ origin moment points towards something like the heart of the industrial capitalist revolution.

What this data suggests to me is two-fold. Firstly, that it seems like the urbanization dynamic is strong and rapidly transforming the social relations of the world on a grand scale. Secondly, more speculatively, that this is a new dynamic. It’s this second point that interests me after beginning the Mumford and in particular after encountering his idea that the City itself is an implosion event, one that operates like a threshold moment the effects of which are a rapid development of productive forces. If the new rise of the city, the rapid increase in urbanization, is a contemporary event then one thing that suggests itself is that a new ‘implosion event’ might be on the horizon or – more likely – might be the horizon within which we are living. Whilst this is deeply connected to capitalist social relations, in may ways it’s also a separate and autonomous dynamic. If the first implosion event of the City brought forth, as Mumford suggests, a quite radical development of the productive forces then it seems reasonable to think that a new implosion event might do something similar. Given that the first implosion event also involved some shift in the collective personality, it would again seem reasonable to extrapolate another such shift. The question that suggests itself, then, is what sort of city psychosis is developing? If the Kingship role is no longer dominant and the ‘paranoid-schizoid’ spectrum that goes with it is perhaps being superseded, what is the city psychosis of the future?

(Citations from Lewis Mumford, The city in history, Pelican 1984.)

*1. I’m talking, very very informally, about interpolating the data in the graph, which would perhaps best be done with some statistical analytical tools. I’m not equipped to do this but just using data points taken at decade long intervals and noting the difference between one decade and another there is, very roughly, something like a 3% increase from decade to decade, although this does increase in more recent decades reaching 4.92% difference between 2000 and 2010. On the basis of a 3% increase decade by decade, and working back from 33.51% at 1960 gives us a 110 year span for the subtraction to hit zero. This is pretty crude and may well hide some obvious problems, so large pinches of salt please, this is just idle speculation on my part at this moment. For example, the difference in growth between decades from 1960 to 2010 increases each year, from 3.08% between 1960 and 1970 to 4.92% between 2000 and 2010. If I were to look at the pattern of this increase, rather than stop at 3%, then I might find that the increase decreases each decade as we move back in time. The increase would then ‘disappear’ at some point, possibly well before 1850, and a ‘stability’ arise in which urban populations remain steady, or relatively steady. This, intuitively, seems far more likely to be the actual case. It seems, intuitively, that there is some point at which urbanisation moves from relatively stable population to relatively dynamic growth, a point which I would imagine coincides somewhat with the rise or industrial capitalism, but I need to find more data sources (and develop my statistical analytical skills) before I could say anything about this. No doubt there is a lot of work already done on this within geography and so I’ll be looking around in that area for some more material. The ‘World Urbanization prospects’ report linked above notes that in 1900 the world urban population was around 13 per cent in 1900, which would still, very roughly, fit the very rough ‘3% of total per decade’ increase model, since that model gives 15% at 1900.

-

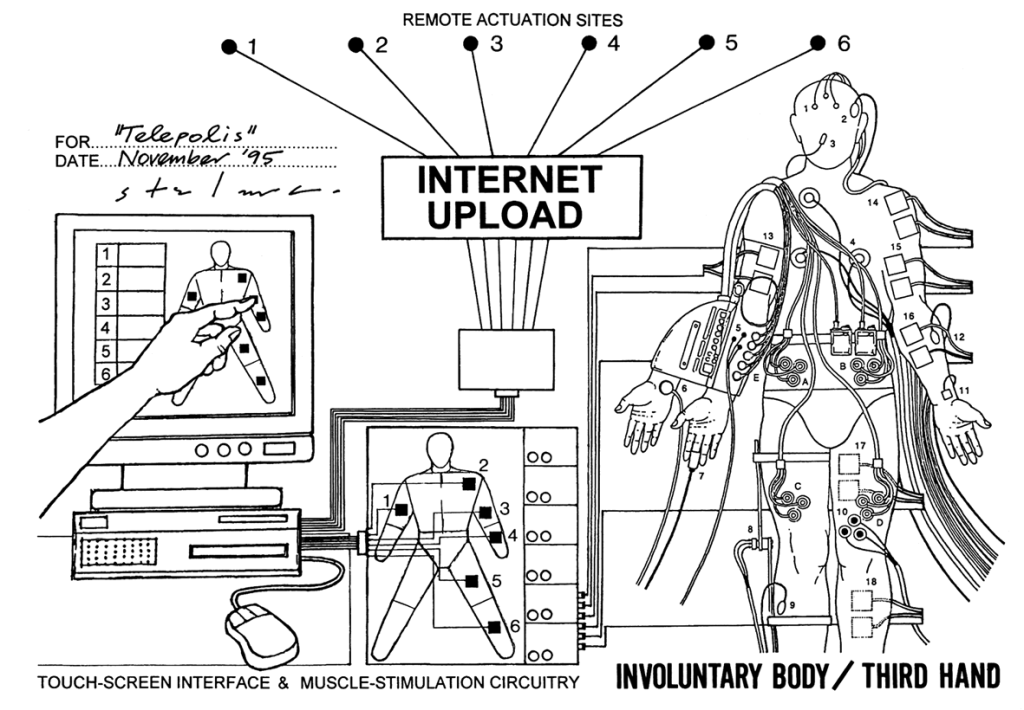

Networked flesh

The question that is pressing in arises from the political problem, the problem of politics in itself, as politics. Put bluntly, why is there such a thing as ‘politics’? It is impossible to avoid this problem because we are always caught within the realm of the political.

An individual member of the human species might find themselves able to step aside from the social, even whilst having inevitably derived their minds from it, but only as a result of the social itself, as a result of some brief area left aside, fallow, by the socialisation of the world. The social spreads, like the viral trace of the species, across the world. This is no anthropocentrism and it is not restricted to the human species – the ‘environment’ is nothing more than the complex totality of the multiple systems of social tracks left by the various species of organic life, some more dense and heavy than others.

The human species treads hardest however. In fact, the human species treads so heavily that it marks a qualititative break in natural dynamics. It is not anthropocentric to acknowledge the specificity of the effects of the human species, the discontinuity between the tracks left by the human species and those of – almost – any other living organism. It borders on the unnatural.

The discontinuity is able to be understood best when encountering the heaviness of the human tread. The traces of the social lie on the surface of the natural, the organic formed within the limits of the inorganic. There are no societies of stones but there are many societies within the stones. The stones form the fuel for the cells, constitute the surface on which the the social traces of the organic leave their mark. Each layer rests on the preceding layer. Yet the human tears through the layers, its weight unable to be borne by the supporting surfaces.

It is this tearing of the surfaces that produces the political. As the human species develops the capacity to rip open the world, as it transforms from the simply social animal, from the collective swarm of flesh that is each organism, it encounters the counter-effect of its increasing capacity for the transformation of the world. This counter-effect is the reconstitution of the human flesh swarm as a new surface, no longer a swarm but now a network of nodes, with a variability of connection, a variability that produces differentials of power across the network. The human swam transforms into a variable network of power and it is as this variability that politics is born. Politics is the form of the variable human network that has gradually replaced the swarm of flesh from which it arises. The type of species that we are is a specific result of the counter-effects of the capacities evolution produced in one form of the flesh. We are, although not in the way Aristotle perhaps thought, the political animal. Our animality is specific because we are a political flesh.

In this situation politics exists not because of needs needing fulfilment, nor because of ideas that want realisation, nor even because of freedom that requires expression. Politics results from the counter-effect of our capacities as an organism. Central to these capacities is collective or social labour. Our break-point with almost all other organisms lies not in language but in social labour. Social labour is not merely a quantitative addition of arms and muscles but is instead the re-organisation of specific forms of work carried out by an organism into a social form of work that is qualitatively more powerful, social labour.

Imagine two groups of human beings in conflict, both equally large. Battle lines are drawn between these two groups as they meet in open territory, maybe a hundred on each side, all armed with little more than bones and clubs. Now if one side has the capacity to become organised, to act as one, to unite their intentions, to follow orders and to ensure each individual animal acts as a cell within a greater whole, then it is inevitable that they will win the battle. The more sophisticated that organisation the greater power it has. Smaller number can overwhelm larger because of their organisation into social labour, into collective labour. No longer a mere mass of flesh the new organisation brings forth a new organism, one that is now not mere flesh but the network of flesh become body. It is this simple, basic, fundamental natural fact about social labour that is the ground of our reality, a reality that is inherently, inevitably, political. Politics exists because social labour exists. Social labour, however, is the catalyst of a counter-effect, the formation of a new body that rests on the shoulders of the flesh and drives it in its own direction. For the most part this networked body of the flesh, this body of social labour, operates blindly, and in that sense politics arrives as an externality, as a new force in the world, one that we are still, desperately, trying to master before it drives us off the cliff of extinction. Our options are to renounce social labour and descend into the earth as flesh once again or to internalise the networked flesh of the body of social labour and become the agents we imagine ourselves to be.

-

We’re all pretty fucked…we must dream and demonstrate the new reality.

With new protests against the fees and cuts being made to Higher Education planned for this Wednesday on what’s being called ‘Day X’ (more information here) it’s necessary to avoid getting drowned in the new slave consensus. The ‘cuts’, the ‘deficit’ and the whole new way in which economics is being organised are presented as obvious, necessary, inevitable. They are no such thing. There are always options. There are realities that we can imagine but these realities must be fought for, both physically and mentally. We must dream and demonstrate the new reality. The only other option is to let the new ‘common sense’ drown us. They will never give it away for free, it has always had to be taken from them by force. This time will be no different. Prepare to fight now. It’s the students and universities at the moment, it will be your hospitals, schools and homes next…and soon.

The following is from from a leaflet currently doing the rounds:“We’re all pretty fucked…It’s not just cuts in education and upping the fees that’s the problem. The problem is that the cuts in general mean we’re all pretty fucked. Whether you’re a student in a F.E college or University, whether you’re a working single-mum, whether you’re self-employed, whether you’re unemployed, whether you’re working a precarious temp job, whether you working a good job in the public sector. The depth of the cuts means most people are going to become worse-off.

There are differing trains of thought that link the cuts to ‘The Crisis’ or ‘The Deficit’ or ‘The Tories’ but for many there is a much more simple truth – it’s just called ‘Life as normal’. The rich have been getting successively richer in this country and the poor have been getting poorer. If the cuts are setting out to re-float a busted economy of over-inflated debt and speculation by taking more and more from the poorer section of the population, well, it’s just more of the same for most people. Poverty, crap jobs, insecurity, health problems – well, that’s just how we’ve been living anyway. But do you feel like politicians will sort it out for you? Do you feel like if you keep your head down and work hard, you’ll be okay? Do you feel scared? Had enough of that shit yet?We’re all pretty fucked…It’s not just cuts in education and upping the fees that’s the problem. The problem is that the cuts in general mean we’re all pretty fucked. Whether you’re a student in a F.E college or University, whether you’re a working single-mum, whether you’re self-employed, whether you’re unemployed, whether you’re working a precarious temp job, whether you working a good job in the public sector. The depth of the cuts means most people are going to become worse-off.There are differing trains of thought that link the cuts to ‘The Crisis’ or ‘The Deficit’ or ‘The Tories’ but for many there is a much more simple truth – it’s just called ‘Life as normal’. The rich have been getting successively richer in this country and the poor have been getting poorer. If the cuts are setting out to re-float a busted economy of over-inflated debt and speculation by taking more and more from the poorer section of the population, well, it’s just more of the same for most people. Poverty, crap jobs, insecurity, health problems – well, that’s just how we’ve been living anyway. But do you feel like politicians will sort it out for you? Do you feel like if you keep your head down and work hard, you’ll be okay? Do you feel scared? Had enough of that shit yet?”

-

Diamond time, daimon time.

In the instant of diamond time duration incarnates and shatters itself. Many types of duration must exist, this seems to be true almost ‘by definition’. Duration is, after all, a multiplicity. Yet the time that fascinates, that holds attention and throws itself upon us, captures and eludes us, is predominantly the moments of diamond time, daimon time. We uncover these moments not through attention – our attention is always held by this time, this daimon diamond time – but through thought. We are forced to think, in the most perfect example of the forcing of thought, by this encounter with diamond time.

The eternal return is perhaps the most celebrated thought of the diamond time. The difficulty is often in extracting any sense of the eternal return from the peculiar and slight traces it left, not least in the peculiar way in which the eternal return is brought back to the moment, to the instant logical game of that which is both there and not there, here and not here. There is no instant of the eternal return since it shatters the moment and explodes the instant, taking us directly into the daimon of time, diamond time.

Time is not a passing, a going or an arriving. Time comes. When it has come it never goes. Almost no human being exists who has not yet had time come to them but there will be some, just as there will some plants, some rocks, some stars for whom time has not yet come – although it will. Aion sits softly on the lap of all and none may avoid the diamond time, no matter may avoid the daimon of time. Aion holds all in time and captures all, in time.

The encounter, however, is that which thought struggles to arrive at. To encounter time is to become shattered by it, at least at its most potent, in its daimon diamond form. We live as time, of course, we project the horizon of temporality up to and into the moment of the possibility of our impossibility but this living of time, this ecstatic temporality, always lacks that which it dismisses as impossible presence. The transcendental condition of ecstatic temporality is diamond time.

No doubt it is difficult to extract thought from its almost inevitable subsumption of diamond time into the subject. Kierkegaard perhaps offers the most abject lesson in this loss. The eternal, encountered as truth, God, Christ and the choice loses Aion in the incarnation of the daimon. We seem to be told that it must be the idea, that which is conjured into existence ex nihilo from the pure power of the subject and yet in this case the instant absorbs time rather than embracing it. It sucks up into the present the eternal that simply couldn’t be here in a moment. Diamond time is instead that which none want to encounter, the explosive truth.

-

Interest and desire

Larvalsubjects has an interesting post on Marx in the academy over here which has generated a lively discussion in which, perhaps unsurprisingly, the question of agency has risen to the fore again. This is still something I find disturbing, something I’m not really able to get a grip on fully, since I tend to understand the problem of agency as responding to something like a desire to answer the question ‘what difference can I make?’. “Where’s the agency“, someone might ask, “in these economic analyses of desire (D&G) or capital (Marx)? Isn’t it all just a huge machine in which I am nothing? And if it is a big machine, how did this machine produce it’s own auto-critique? Isn’t it really the break, the rupture (of the subject), that we need to theorise? Isn’t consciousness really the most important fact in reality since it is inexplicable by reality? Me, I’m important, surely – doesn’t my analysis do anything, offer anything – don’t I have the answers, or at least the right to produce answers or the possibility of finding them?” I’m inclined to dismiss these questions out of hand as the whining desire of a resentiment-filled petit-bourgeois who thinks they’re ‘in charge of their life’ in the first place but have to recognise that at least some of the charge invested in this response is disproportionate and perhaps related to the other peculiar investments I find myself bound to (revolution, majik, sex).

Larvalsubjects has an interesting post on Marx in the academy over here which has generated a lively discussion in which, perhaps unsurprisingly, the question of agency has risen to the fore again. This is still something I find disturbing, something I’m not really able to get a grip on fully, since I tend to understand the problem of agency as responding to something like a desire to answer the question ‘what difference can I make?’. “Where’s the agency“, someone might ask, “in these economic analyses of desire (D&G) or capital (Marx)? Isn’t it all just a huge machine in which I am nothing? And if it is a big machine, how did this machine produce it’s own auto-critique? Isn’t it really the break, the rupture (of the subject), that we need to theorise? Isn’t consciousness really the most important fact in reality since it is inexplicable by reality? Me, I’m important, surely – doesn’t my analysis do anything, offer anything – don’t I have the answers, or at least the right to produce answers or the possibility of finding them?” I’m inclined to dismiss these questions out of hand as the whining desire of a resentiment-filled petit-bourgeois who thinks they’re ‘in charge of their life’ in the first place but have to recognise that at least some of the charge invested in this response is disproportionate and perhaps related to the other peculiar investments I find myself bound to (revolution, majik, sex).One of the things that I thin I agree with larval about is that the emphasis of thinkers such as Badiou, Laclau, Ranciere and Zizek seems to be inverse to that of Marx – “Don’t these positions [Badiou, Laclau, Ranciere, Zizek] postulate that change proceeds via consciousness, rather than consciousness, thought, emerging from modes of production?” larval asks.

-

beware desyr: anti-oedipus reading notes

One of the re-occurring problems that Deleuze & Guattari address within Anti-Oedipus (AO) is that of the apparently self harming act. This is perhaps most clearly indicated in the way in which they return to the ‘desire for fascism’ within the masses that Wilhelm Reich attempted to address in his book The mass psychology of fascism. Reich, whom D&G declare “the true founder of a materialist psychiatry” (AO: 129), was unsatisfied with any theoretical explanation of the rise of fascism that failed to account for its popular support. They phrase this in terms of desire – “Desire can never be deceived. Interests can be deceived, unrecognised, or betrayed, but not desire. Whence Reich’s cry: no, the masses were not deceived, they desired fascism, and that is what has to be explained” (AO: 279). The argument is a attempt to allow reality to speak, to let the facts back in, in particular the unpalatable fact that there was this support for fascism (this desire). Such a fact, the argument presumably goes, means that we are faced with the options of (i) either those who voted and marched and applauded the fascists were somehow duped or else (ii) they willingly and knowingly wanted this state of things (which is taken to be a kind of contradictory situation since it is ‘against their own interests’ for the masses to desire fascism). Unlike a simple despotism in which the autocrat installs themselves through violence, perhaps aided in some sense by passivity, the fascist regime came to power through a popular passion, through the desire of the masses. This poses the problem of why people desire that which is against their own interests, why people desire that which oppresses them?

-

The problem of the program

Notes on revolutionary Marxism

Notes on revolutionary MarxismThe central tenets.

(beginning from the ‘Founding Statement’ of the Trotskyist group ‘Permanent Revolution’ to be found online at http://www.permanentrevolution.net/?view=entry&entry=779, accessed 15.11.07)

- Belief in communism, “using Karl Marx’s rough guide to communism – from each according to his (or her) ability, to each according to his (or her) need – as its starting point”.

- Belief in revolution – violent revolution – because (a) the state will defend its interests and (b) wholesale change is necessary (radical break) rather than reform.

- Belief in the working class as the ‘agent of change’ – the only revolutionary class.

- Belief in the need for a revolutionary, internationalist party.

- Lineage – tradition (Paris Commune; Marxist wing of 1st International; Left wing of 2nd International, the Bolsheviks and Rosa Luxembourg rather than the Mensheviks; 3rd International (first four congresses) before Stalinisation onset; 4th International – then debate.

- The need to continue to develop a program “in the light of experience, the supreme criterion of human reason”. (Empiricism) It is on the basis of this programmatic development that further distinctions are then made (i.e.; the decline or ‘degeneration’ of the 4th International – in the case of PR this involves classifying the ‘United Secretariat of the Fourth International’ (USFI) as having ‘collapsed into opportunism).

This takes us up to point 6 of the ‘founding statement’, which consists of 14 points in all. The following 8 points all, to one degree or another, mark the analytical differences that then form the necessary conditions for the new move (the founding of a new group).