This post was recently found in the drafts folder, lost in the database for some five years. Meh.

1.

The image is already fading. This is perhaps the only thing we might want to accelerate within capitalism, although capitalism is not the source of the image, or the fading. Both image and fading have, however, been transformed and accelerated, in some sense, through capitalism.

It is not to excuse capitalism from any of its horrors to ask, as Marx clearly did, what is capitalism productive of? The horrors are the most important, the specificity of those horrors compared to analogous events in other socio-economic forms. Of less importance however, although still not without importance, there are numerous other effects of capitalism. The vampire is not without its virtues. The question is, is there some virtue of capitalism that we might want to increase in intensity, so as to provide a route through which to escape capitalism as such.

Roughly, the answer would be yes. Capitalism does something that must be acknowledged to be a virtue – it makes knowledge productive in a way that is unprecedented. Science, a concept that is highly charged, is internally compromised by the sheer voracity of the capitalist virtue of making knowledge productive. A limit is revealed, the limit of the transparency of knowledge.

The image is already fading. The image of the human, the image of thought, the image of the future. Walking down London Road, high on the walls, stands the reminder of a time before neon and the public relations industry, the ghost sign of W.J.Andrew, Family Grocer, Provision Merchant. Tomorrow someone will discover that the new filter setting on their phone is called ‘ghost sign’.

There’s a curiosity between generations in popular music. The eighties and nineties return, like the repressed, in something that might seem like nostalgia, as though there is no future for the past to fade away from. It cannot be nostalgia, since that would assume there was some time when today was listening to the past, when in fact today’s listeners hadn’t even been born. It isn’t nostalgia, or any other lack. It is instead the flatness of time gradually appearing, through the expanding database. Database flatness, edges of the former times now appear as ragged, those times now, those befores, are less partially inscribed in images and data than now. Yet it is a transition phase, towards the new database times. (Or barbarism). Forward or death, yet there will be no more forward in database time, simply coordinate space. Without the ‘forward’ it smells like death. The problem is whether the future is a future with or without temporality? The image of time is fading in the face of the database. Everything will be dated, but nowhere will time be found. (A new aeon).

“Is there not already in the Stoics this dual attitude of confidence and mistrust, with respect to the world, corresponding to the two types of mixtures – the white mixture which conserves as it spreads, and the black and confused mixture which alters? In the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, the alternative frequently resounds: is this the good or bad mixture? This question finds an answer only when the two terms end up being indifferent, that is, when the status of virtue (or of health) has to be sought elsewhere, in another direction, in another element – Aion versus Chronos”. (Logic of Sense, 23rd Series of the Aion, p162).

The ‘black and confused mixture which alters’ has flown its flag, still flies it, yet indifference reigns. Even when indifference is not the order of the day, amongst those activists and organisers and leftists for example, their stance is now so hysterically moral and lacking any future as to suggest it is no longer actual rebellion but merely the inverse symptom of generalised indifference. Moral outrage infects what were once the ‘forces of the future’ with a proto-fascism that will spawn when the conditions call for it. The demand is to negate the forces of capitalism with the idea of the future, a conception of another world, a transcendence of property and profit, yet without weapons (not words) such negation is, like all negation, hollow. The candle in the eye of the cow.

Is this a good or a bad mixture? The image is fading, time is shifting, temporality undergoing a transition as fundamental as the introduction of clock time and Saint Monday may even make it’s return. The aion of capitalism has offered us a peculiar time, needs to offer us a peculiar time, at once Chronos crossing labour but simultaneously Aion forcing exchange. As each moment becomes measured and quantified, de facto, in labour time, each moment also becomes exchangeable, de jure, for any other. In this tense dynamic the image is already fading.

2.

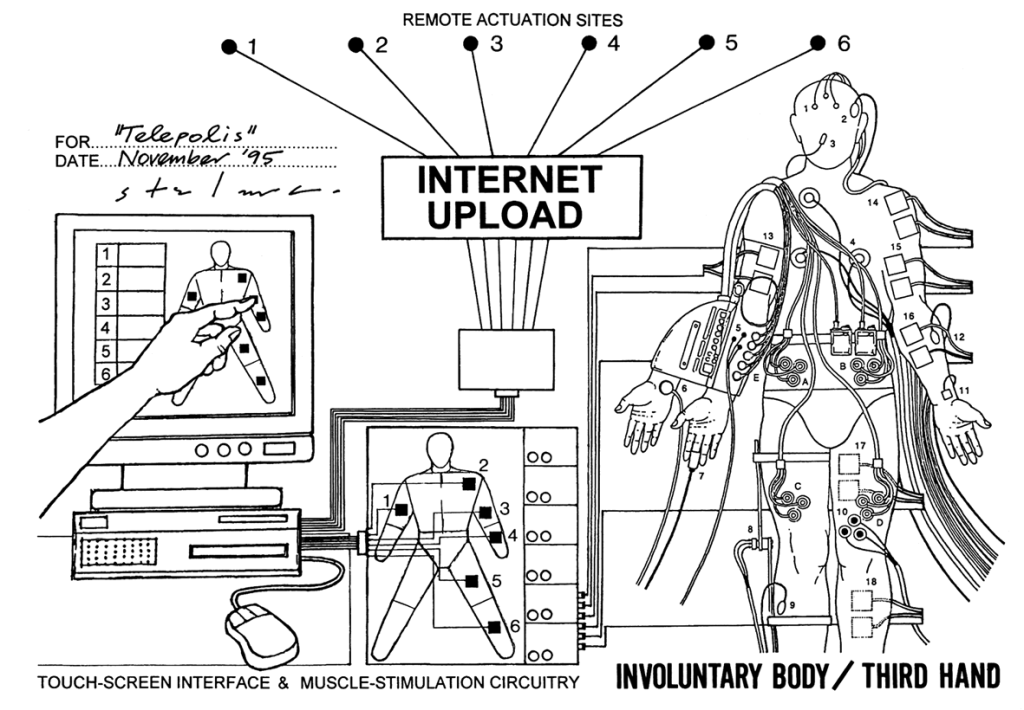

How can we distinguish the image from the event? Through it’s fading. This intimacy of the paint peeling, the emulsion yellowing, the edges fraying, the memory failing, this intimacy of fading is in part the ground of the image. An image that never fades is simply no longer an image. Yet what if this fading itself was becoming ungrounded, fading out, as we cross-fade into the new form. The black mixture that alters has wreaked havoc (through the ‘digital revolution’) on the image, that black mixture made up of the bodies of cameras and lcd screens and red buttons, drifting across the earth and our eyes.

During the late nineties there was an argument amongst film-makers, particularly those who had come into the practice in part because of the digital revolution (the horrors of Blair Witch as symptom). The dominant position of this argument essentially claimed that emulsion-based techniques were little more than neutral tech that would soon be superseded by the CCD improvements. ‘CCD’ stands for ‘Charge Coupled Device’. Within digital cameras the CCD is often referred to as the ‘chip’ of the camera, although it is not the same sort of ‘chip’ that is found within a modern PC. A CCD essentially converts input into electrical charge, as distinguished from emulsion techniques where the film would converts input into chemical charge. The pro-digital proponents pushed the propaganda that the CCD process was, effectively, better than emulsion because it was more accurate. Arguing for emulsion was reduced to ‘clinging to a fetish’. The debate was framed into a ‘forwards/backwards’ push, the digital proponents akin to proto-accelerationists, the emulsion fans converted into something like a luddite technician.

The real question, however, was always the one of the virtues of the mixture. The real error was the functionalism of the proto-accelerationist pro-digital fans, the idea that image capture and production was a functional process. Like all good functionalists, if the process is a function then it is possible to instantiate it in multiple forms and, whilst these forms might have some specificity, this ‘idiosyncrasy’ of the technology was little more than noise in the functional process that could be eliminated in time. Given the right CCD and the right light the mixture would be functionally indistinguishable from emulsion based processes. Digital could be made to look like film. Except it couldn’t, not really, and once that was realised it was soon argued that such attempts to ‘make digital look like film’ were redundant aesthetically.

The real mixture into which the luddite emulsionites and the accelerationist CCD-lovers were thrust was not driven by image capture and production, it was instead driven by commodities, the basic cell of the capitalist body. The new digital cameras were a boost in commodity forms, a new gadget to get, crashing the actual cost of image production and capture. The ‘digital revolution’ occurred not because of the advance of digital technology but because of the cost of film-making. The debates about fidelity, dynamic range, colour constancy, focal depth and various other arcane aspects of the tech were all strange symptoms of a process that demanded the sale of camcorders.