(These notes provided the basis for a talk I gave to the A2Z group in London, March 31st 2017. I have uploaded the fuller set of notes as a PDF here)

“I am interested”, Guattari says, “in a totally different kind of unconscious. It is not the unconscious of specialists, but a region everyone can have access to with neither distress nor particular preparation: it is open to social and economic interactions and directly engaged with major historical currents”. It is useful to think about Guattari’s interest by considering what he says in another essay – “molecular analysis is the will to a molecular power, to a theory and practice that refuses to dispossess the masses of their potential for desire”. The schizoanalytic practice is thus a means by which desire is brought front and centre without it being subsumed under the priests of interpretation.

This desire on the part of Guattari, to liberate the role of desire from the prisons of interpretation, is no doubt tricky to embrace. As he notes in the essay ‘Everybody wants to be a fascist’, the core of this problem lies in the collective reality of desire. At one point he reflects on the performative contradiction that might be thought to exist in the situation of an individual lecturer offering this schizoanalytic account – “in reality, everything I say tends to establish that a true political analysis cannot arise from an individuated enunciation” because “the individuated enunciation is the prisoner of the dominant meanings. Only a subject-group can manipulate semiotic flows, shatter meanings, and open the language to other desires and forge other realities”.

This problem, of the individuated enunciation in relation to the group ear, becomes clearly visible when Guattari remarks, in the same essay on fascism, that “what’s the use of polemicising: the only people who will put up with listening to me any longer are those who feel the interest and urgency of the micropolitical antifascist struggle that I’m talking about”. This acute sense of the limitations of those who will ‘put up with’ him appears to echo the actual practice of engagement with strange and psychotic discourses, no doubt reflecting Guattari’s continual concrete engagement with psychotics in institutions like La Borde. The difficulties of dealing with the repetitions of psychotic language or behaviour often express themselves in terms of precisely this capacity to ‘put up with’ things, a capacity that the wider socius – outside of a clinical setting – generally lacks. One of the main difficulties someone with a ‘mental health problem’ encounters is the wearing down of their personal relationships as people refuse to ‘put up with’ behaviours and language that disrupts the smooth functioning of the social machine, a difficulty that is shared by anyone who speaks, writes or thinks in a way that doesn’t conform to the easy-mode game of social cues and interactions. Most people prefer their games set to easy-mode. So when Guattari – who is often identified as one of the ‘deliberately obscure’ thinkers – acknowledges that he is difficult to listen to it might be thought that he is acknowledging the idiosyncrasies of his style. It is, however, not simply the style of his language but the content of his thought that is what becomes difficult to listen to.

The relation between the specific enunciator and the group ear, constitute the real terms of actual enunciation. It stands in contrast with the “universal interlocutor”, that great imaginary face of reason in front of whom every rational speaker is supposed to stand, awaiting judgement. Analysis, reason, explanation, all operate, for the most part, inside this system of the ‘judgement of God’, in which the particularity of the statements are meant to be swept away in favour of the universality of the supposed ‘truth’ they attempt to articulate. Yet this strange, abstract model of reason hides in plain sight a simple lie, which is that what is said is what matters. This lie, that it is what is said that matters, removes that crucial and seemingly incontrovertible reality of the ear. In practice the users of language constantly negotiate with the ear, constantly re-speak their words as they negotiate with the ear of their interlocutor, a negotiation that constitutes the basis of ‘personal relationships’. The to-and-fro between one individual and another in an intimate relationship reveals the reality of the ear in the word – what the other hears matters more than what words were used and the words are highly fungible in the struggle to make oneself heard or to hear what someone means. Anyone who fails to realise this will have many failed relationships. What you think you said matters less than what they know they heard.

Whilst this problem of the ear is acute in the relations people have with the ‘psychotic’ individual, it is prevalent to one degree or another in all talk, in all discourse. It’s not a clean problem, however, not an error that can be corrected. Rather it’s a dirty problematic, one that refuses to be washed away and which calls for other strategies, ones that cannot be prescribed but which must be acquired. When Guattari says that the ones who will put up with him are the ones ‘who feel the interest and urgency’ of the problem he is addressing it is crucial to hear this emphasis on feeling. The collective conversation, this coming together of mouth and ear, is grounded in this ‘vague sense’ that we ascribe to feelings. It may be true that I feel before I think but what is forgotten is that I don’t stop feeling once I begin to think. Thought is only ever alive and real, actual, when it is within a specific network of feelings. There is no actual thought in the pages of a book left on the shelf, at best only virtual thought. There is no thought without a tone of existence, without an ‘affect’ within which it is both produced and constrained.

It’s easy to find much talk of ‘affect’ in modern philosophy and critical thought, although it is perhaps waning as the flavour of the month. Yet the connection between ‘affect’ and the ‘schizoanalytic unconscious’ is strong and thinking them together can amplify their capacity to be useful tools in making the world thinkable. In the contemporary world the problem of a political future distinct from the one we live in is deeply constrained by the problem of ‘thinkability’. We hear the idea that “a radically different future is unthinkable”, a point that has been made enough times now to become almost second nature to many. Yet the problem of the unthinkable future is best encountered not through pessimism but through a kind of joy, a joy that rests in the fact that thought is explosive. What I mean by this is that thought operates not in a causal sequence but in terms of excessive moments, those breakthroughs, sudden glimpses, the shifts and slides of the ‘aha!’ moment, what sometimes goes under the name of ‘insight’, a term not without it’s own difficult implications. In this situation if the problem of the moment is that the future is unthinkable then, at the same time, this blockage is deeply fragile. All it takes is for the thought of the future to arrive for the damn to burst.

This ‘all it takes’ is not nothing, however, it is not there to suggest an easy way to thinking the future but rather to indicate that peculiar fragility which perhaps cannot be perceived in the present but that, nevertheless, we can wager exists. The wager becomes easier to make if the stakes are placed on the right horse and it is in this that the role of ‘affect’ and the ‘schizoanalytic unconscious’ can help, predominantly by replacing the ‘cognitive priority’ conception of consciousness. Within this conception of consciousness thought is conceived as a series of moments,usually moving from starting point to conclusion, whereby an ‘input’ is transformed into an ‘output’. This model of transformation is deeply delusional and massively idealistic. It assumes some kind of autonomous module that exists within the ‘mind’ and which mediates the input/output relations, relations in the broad sense between ‘world’ as input and ‘behaviour’ as output. Instead of such an abstractly autonomous module, consciousness is instead a kind of shape, one that exists within a network of relations and which possesses only as much autonomy as is possible within the particular state of relations. That network of relations which places limits of the amount of autonomy possible is what can be thought with the concepts of ‘affect’ and the ‘schizoanalytic unconscious’. The material body that thinks exists inside the social relations it is organised into, which it expresses as a particular set of affects (feelings) that in turn constitute the landscape of its possibilities, it’s ‘schizoanalytic unconscious’.

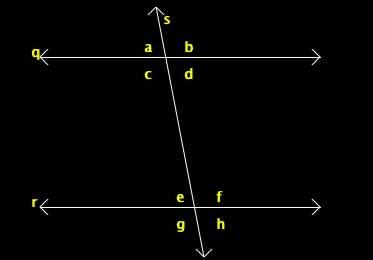

These four elements – the material body that thinks, the social relations, the sets of affects and the landscape of possibilities – all operate to constitute a world and each is malleable to a greater or lesser degree. A political thought which takes each seriously and which understands them to be moments of the articulated whole needs to think of causality less as a sequence of temporal moments and more as a fluid articulation of complex connections between points, as a set of vertices and edges. The shape that is constituted by the vertices and edges is the contemporary world of the subject, it is, in effect, the shape of consciousness at any particular moment. Within contemporary capitalism the shapes of consciousness continually undergo a set of pressures that attempt to ‘push’ such shapes into a particular mould, that attempt to fit square pegs into round holes, or more exactly that attempt to fit variable pegs into round holes. The round hole is constituted by ‘capital’, by an abstract, non-conscious yet non-material force – a law of production – that is capable of direct effect on the points and lines that form the shape. It’s capacity to deform the shapes of consciousness rests in the force it brings to bear on the shapes of consciousness, forces which produce, amongst others, the idea of the ‘wage labourer’, but which operates, fundamentally, as the primary force acting on contemporary consciousness. To that extent our problematic can be stated quite clearly – capitalism and contemporary consciousness are connected, but is the connection contingent or necessary?.