(Caveat – reading notes are NEITHER summaries NOR commentaries, they operate as individuated sets of connections and references, individuated on my own research paths.)

Gary Genosko, A-signifying semiotics, The public journal of semiotics II (1), January 2008, pp 11-21

(I’ve been struck by the a-signifying and machinic recently, so this is part of some research into that area.)

The essay is short and tight, with the use of ATM / magstripes to illustrate the role of a-signifying semiotics (ASS). ‘Reorientation’ argument, attempting to place AAS on the table for semioticians. (1) suspend hierarchy of sign/signal, where signal is lower in status because of capacity to be “computed quantitatively irrespective of their possible meaning” (def. Eco), (2) quantitative / machinic aspect of signals to be theorised as positive, not negative. Signals as subset of ASS, the latter theory being what underpins the retheorisation of the signal.

Signals are ASS to the extent they transmit information. But ASS [“non linguistic information transfer” (p12)] fundamentally are: non-representational, non-mental, strict and precise. Operation through ‘part-signs’ (aka. particle-signs, point-signs). No ‘lack’ of meaning in ASS (not “denying something to someone” p13) and not reducible to a behaviourist model. ASS part of the route by which the Ucs. can be theorised outside structuralist and psychoanlaytic models. (The ‘exit from language’).

Signifying semiologies (SS) form on “the stratified planes of expression and content” which are “linguistified”. The SS structured by “the axes of syntagm and paradigm” (syntagmatic = series of terms (c0-present), paradigmatic = constellation of terms, indeterminate (lacking co-presence). Bosteels suggests ASS ‘add a third, diagrammatic axis’ but “this is a conservative maneuver, at best” (p14). Nor enough to take ASS as ‘disturbing’ binary of SS, as this still allows despotic signifier to reign – “It would be easy to trap a third axis in the prodcution of a certain kind of subjectivity if it was always linked to a specific expression substance like a despotic signifier. This despotism may be deposed if it is linguistic, but it’s relation to power, even the power of the psychoanalyst, is not vanquished” p14). [The despotism that comes to mind here is that of the therapist, guru, ‘master’, even if they use extreme non-linguistic forms (Primal therapy perhaps as an example here? What about art therapy, eg the LSD therapy with holocuast survivors, or ‘art brut’? A connection with the logic of sensation here perhaps but a very different ‘tone’ in that concept compared to ASS?).]

[ASS deployed in ‘cultural’ analysis would appear to be strictly opposed to the Geertzian model but would they ground an ‘experimental science in search of law’? That seems unlikely, but if not then what prevents law- or function-procedures from operating or being established?]

ASS ” ‘automate’ dominant significations by ‘organizing systems of redundancy’ on the levels of expression and content: automation entails normalization, invariance and consensus” and also “stabilization”(p14) and as such are inherently political (micro-p) rather than ‘scientific’. (The ASS ‘operationalise local power’ and such operations are ‘encoded in the magstripe‘.)

SS in fact rely upon ASS, the former being deployed as ‘tools’. [Is there here an ‘ideology’ type idea of the SS as ‘illusions’ benefiting, for example, class interests. The central difference being that there are no ‘ideas’ necessary in this type of activity, no ‘ideology’ is needed for ‘ideology’ to operate. Ideology, itself, as a kind of SS, deployed by an ASS. Is this a latent / manifest divide again?]

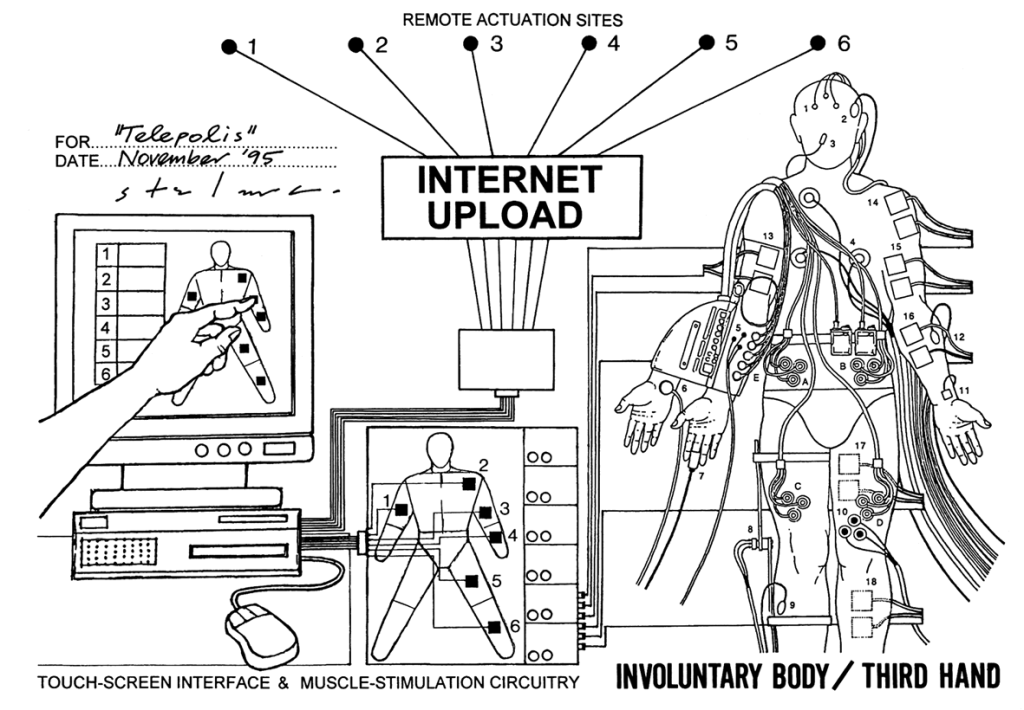

ASS is machinic, machine is not limited to technical devices but despite this Guattari’s “repeated description of how the a-signifying semiotics trigger processes within informatic networks highlights the interactions initiated with a plastic card bearing a magnetic stripe in activating access to a bank or credit account, engaging an elaborate authentication process, makes it clear that we are dealing with a complex info-technological network.” (p15) [This does sound as though there is something specific to modern capitalism with regard ASS, but even if ASS derived from or depended on ‘complex info-technological networks’ (ITN) it would seem appropriate to describe the brain as just such an ITN, particularly once engaged in technics, particularly if that technics is one of things rather than ideas (here I’m thinking of Barad – “Apparatuses are not Kantian conceptual frameworks: they are physical arrangements” – Barad, 2007, 129). There is something in the ‘trigger’ that makes me think of neuro-biological structures as well. This would push ASS into a space where they might perhaps be able to ground an Ucs on something other than meanings / language. Still, even if an ‘extended’ brain (via technics), how far would this be capable of being operationalised? Into the Earth itself? Or stopping at the World? (ASS of evolutionary dynamics, extended phenotype perhaps, pushing into the Earth and beyond the World?)]

“Triggering is the key action of part-signs”. (p17). Guattari cited – “algorithmic, algebraic and topological logics, recordings and data processing systems that utilize mathematics, sciences, technical protocols, harmonic and polyphonic musics, neither denote nor represent in images the morphemes of a referent wholly constituted, but rather produce these through their own machinic characteristics” (p18). Constraint does not close the machine but is the condition of its productivity within the space of ‘machinic potentialities’.

The role of triggering – Guattari “extricates himself from the Piercean trap of subsuming diagrams under Icons” (p17), distinguishing between the semiotic regimes of the image (symbolic) and the diagram (a-signifying). This is a “relatively straightforward … splitting of diagrams from icons and substitution of reproductive fro productive force” (p18).

Brief paragraph on the Hjelmslevian form/content appropriation that Guattari makes (p18-19).

Final section (V) on the connection to politics (an ‘essential’ connection) via the role of information and organisation. “Repetitive machinic signaletic stimuli are the stuff of the info capitalist technoverse” (p19). The ‘means of escape’ [always this question] – “the key to overcoming this straightjacket of technological deterministic formal correspondence would be to look at the alternative ontological universes opened by a-signifying semiotics and the kind of subjectivities attached to them” (p20).

Other references:

Karen Barad, Meeting the universe halfway, Duke 2007.