I missed the reading group on October 13th, when they discussed Chapter 2 (1914: One or several wolves), and so I’m turning to the Chapter 3 10,000BC: The geology of morals. I will return to Chapter 2 when I have time. We read the first half of Chapter 3 on October 20th, up to but not including the paragraph that begins ‘Most of the audience had left…’ (ATP 57) and will continue with the remainder of Chapter 3 next week. As a reminder, these notes are in no way a report of the reading group, rather they are my notes and thoughts which will be informed by the discussion there, but all mistakes and errors are my own.

The ‘double articulation’ that is the focus of this chapter is that of the ‘codes’ and ‘territories’ that are probably quite familiar to readers of D&G. The processes of code and territory produce many of those curious ‘jargon’ terms so hated by critics, terms like decoding, overcoding, surplus value of code, deterritorialization, reterritorialization. At heart, these two processes, of code and territory, involve processes and because of this the dynamics of those processes, whether they are opening or closing dynamics, are central to D&G’s discussions. What purpose do these processes have in the analytical model of schizoanalysis? They are replacements or alternatives for more traditional philosophical concepts of ‘form’ and ‘content’ and are intended, I think, to transform the analytical categories that are used to understand specific ‘objects’ (concepts) of discussion. So, when talking, for example, about the ‘nature of subjectivity’, we could analyse it in terms of codes and territories rather than in terms of language, experience, ideology, genealogy or substance. We might presumably do something similar for concepts such as ‘nation’, ‘class’, ‘freedom’ or ‘truth’.

The ‘double articulation’ that is the focus of this chapter is that of the ‘codes’ and ‘territories’ that are probably quite familiar to readers of D&G. The processes of code and territory produce many of those curious ‘jargon’ terms so hated by critics, terms like decoding, overcoding, surplus value of code, deterritorialization, reterritorialization. At heart, these two processes, of code and territory, involve processes and because of this the dynamics of those processes, whether they are opening or closing dynamics, are central to D&G’s discussions. What purpose do these processes have in the analytical model of schizoanalysis? They are replacements or alternatives for more traditional philosophical concepts of ‘form’ and ‘content’ and are intended, I think, to transform the analytical categories that are used to understand specific ‘objects’ (concepts) of discussion. So, when talking, for example, about the ‘nature of subjectivity’, we could analyse it in terms of codes and territories rather than in terms of language, experience, ideology, genealogy or substance. We might presumably do something similar for concepts such as ‘nation’, ‘class’, ‘freedom’ or ‘truth’.

There is something more than merely a ‘model’ at stake, however, at least the opening of the chapter appears to pose the problem in more fundamental terms. The double articulation of codes and territories – for which the Lobster is an image – is presented as a way to understand the process of ‘stratification’. Stratification arises ‘simultaneously and inevitably’ (ATP 40) alongside or within the ‘unstable, unformed matters’ that constitutes the Earth. Stratification consists “of giving form to matters, of imprisoning intensities or locking singularities into systems of resonance and redundancy, of producing upon the body of the earth molecules large and small and organising them into molar aggregates” (ibid). In other words, stratification – operating through the double articulation of codes and territories – is the process through which something like a ‘primal flux’ comes to be ordered, a process through which the dynamic flows of matter form something like ‘objects’ or ‘substance’.

Immediately, however, we must double the doubling, specifically we have to take into account the pairing of ‘content’ and ‘expression’ and the fact that each of these terms is, again, doubled. If ‘matter’ is the “unformed, unorganised, nonstratified, or destratified body and all its flows”, then ‘content’ refers to “formed matters, which would now have to be considered from two points of view: substance, insofar as these matters are ‘chosen’, and form, insofar as they are chosen in a certain order (substance and form of content)” whilst ‘expression’ refers to “functional structures, which would also have to be considered from two points of view: the organisation of their own specific form, and substances insofar as they form compounds (form and content of expression)” (ATP 43).

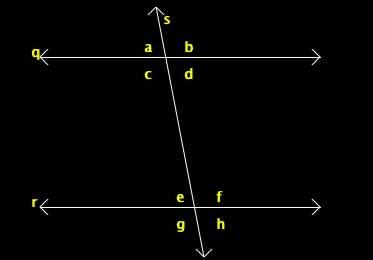

“Double articulation is so extremely variable that we cannot begin with a general model, only a relatively simple case. The first articulation chooses or deducts, from unstable particle-flows, metastable molecular or quasi-molecular units (substances) upon which it imposes a statistical order of connections and successions (forms). The second articulation establishes functional, compact, stable structures (forms), and constructs the molar compounds in which these structures are simultaneously actualised (substances). In a geological stratum, for example, the first articulation is the process of ‘sedimentation’, which deposits units of cyclic sediment according to a statistical order: flysch, with its succession of sandstone and schist. The second articulation is the ‘folding’ that sets up a stable functional structure and effects the passage from sediment to sedimentary rock.” (ATP 41)

The first curiosity here is this use of such a ‘geological’ model. It seems, on the face of it, that a model derived from a natural science such as geology is going to produce category mistakes if we deploy it in analysis focussed on the ‘human’. Aren’t issues of meaning, signification, sense and intention more relevant to political and social analysis? Such an assumption begs the question, despite it’s apparent obviousness to many people who are happy to merely assert some human exceptionalism as though it were incontrovertibly the case. Even if we don’t beg the question, however, there seems something a little odd about deploying ‘geological’ models in a text that purports to be about ‘capitalism and schizophrenia’. How might we connect a ‘geological’ concept of stratification to something ‘human’? Whilst this question already assumes too much importance for the human, it might be useful as a way of being able to understand what political or social implications there are in ATP, and that itself might be necessary because I’m assuming that – broadly speaking – most of the people interested in ATP are interested in such ‘human’ issues rather than in subjects such as geology, which is not to deny that there is also possible interest in the text for geologists.

There is a second curiosity, however, which is that the specific ‘stratum’ that is addressed in the chapter is not geological or even human but the organic. The chapter is staged as a lecture being delivered by Professor Challenger, a character from Arthur Conan Doyle stories. At one point there is clearly a sense of a merging of Challenger with the authors of ATP, most notably when Challenger is described as having “invented a discipline he referred to by various names: rhizomatics, stratoanalysis, schizoanalysis, nomadology, micropolitics, pragmatics, the science of multiplicities.” (ATP 43). Amusingly the text continues as follows – “Yet no one clearly understood what the goals, method, or principles of this discipline were.” (ibid). To return to the discussion in the chapter/lecture hybrid, what we’re reading soon moves from the rather abstract account of double articulation to something more concrete – “the question we must ask is what on a given stratum varies and what does not? What accounts for the unity and diversity on a stratum?” (ATP 45) and this question focusses on the ‘organic’. At the heart of this is a discussion (ATP 45-49) that begins from a staging of the debate between Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire and Cuvier. An account of this debate is given – “Challenger imagined a particularly epistemological dialogue of the dead, in puppet theatre style” (ATP 46) – the purpose of which, however, is to present the ‘paradigm shift’ introduced by Darwin. At the end of the staged debate we find the following passage:

“We have not even taken Darwin, evolutionism, or neoevolutionism into account yet. This, however, is where a decisive phenomenon occurs: our puppet theatre becomes more and more nebulous, in other words, collective and differential. Earlier, we invoked two factors, and their uncertain relations, in order to explain the diversity within a stratum – degrees of development or perfection and types of form. They now undergo a profound transformation. There is a double tendency for types of forms to be understood increasingly in terms of populations, packs and colonies, collectivities or multiplicities: and degrees of development in terms of speeds, rates, coefficients, and differential relations. A double deepening. This, Darwinism’s fundamental contribution, implies a new coupling of individuals and milieus on the stratum. (ATP 47-48)”

It is this ‘new coupling of individuals and milieus on the stratum’ that is the link between ‘geology’ and ‘morals’ and through which the first curiosity I mentioned is in some sense made clearer by the second. It is this ‘new coupling’ that offers a productive and ‘transferable’ set of categories, ones that can move across the analysis of the processes of geological sedimentation into the analysis of the processes of individuation more generally, although quite how generally is still up for question as there is plainly no direct and obvious route from Darwinism to politics or sociology, or at least no direct uncontested route since at the very least we can find ‘socio-biology’ suggesting one, albeit highly contested, possibility of generalisation. The route to generalisation taken by ATP, however, is distinct from any socio-biology I’m aware of, primarily because it’s primary category of generalisation is to be the ‘abstract machine’.

The problem that is posed as the motivation for Challenger’s discussion is the “unity and diversity of a single stratum”, what is it that enables a single stratum to have a “unity of composition, which is what allows it to be called a stratum” (ATP 49). This problem directly arises from the ‘science of multiplicities’, what I called the ‘method of the rhizome’ in my discussions of the first chapter of ATP. If ‘multiplicity’ is to be taken as a substantive and in doing so replace problematics involving a ‘dialectic’ between the One and the All, then the ‘problem of individuation’ can be posed in terms of how it is possible to call something a thing in the singular, in this case, how is it possible to discuss a stratum from within a model of the double articulation of stratification, where at any moment there is always more than one involved – the double bind of double articulation.

In the paragraph that starts “To begin with, a stratum does indeed have a unity of composition…”, just following a brief remark re-emphasising the staging of the chapter as a lecture by Challenger, an initial move to introduce the abstract machine is made. Here the process of individuation of a stratum is posed in terms of “a change in organisation, not an augmentation” and the factors involved in a relation between a stratum and a substratum are reciprocal rather than hierarchical, hence why D&G declare that “we should be on our guard against any kind of ridiculous cosmic evolution” (ATP 49). A substratum is posed as a milieu, as an “exterior milieu for the elements and compounds of the stratum under consideration, but they are not exterior to the stratum” (ibid). They try to illustrate this reciprocal relation of exterior / interior in the composition of a stratum by first offering the example of a crystalline stratum developing from the seed and medium and then move to claim that “the same applies to the organic stratum: the materials furnished by the substrata are an exterior medium constituting the famous prebiotic soup, and catalysts play the role of seed in the formation of interior substantial elements or even compounds” (ATP 49-50). Crucially there are three elements at work here, viz. (1) the (exterior) milieu, the molecular materials (2) the (interior) seed, interior substantial elements, and (3) the limit of exchange between the two, the “membrane conveying the formal relations”, or surface. The abstract machine is the ‘synthesis’ or result of the reciprocal relations between these three elements and is given the name of Ecumenon in contrast to what they call a Planomenon.

Before moving forward it’s worth considering why this abstract machine is important. It offers us the mode of individuation that is going to be able to explain the existence of organisation from the background of a disorganised flow of matter, although ‘explain’ might be too strong here – it offers an account or descriptive framework. It’s worth noting that the whole discussion of stratification within which this existence of the abstract machine plays its role is offered from a factical staring point, that is, the ‘simultaneous and inevitable phenomenon of stratification’ is simply offered alongside the account of the ‘body without organs’, “…the Earth, – the Deterritorialized, the Glacial, the giant Molecule…” (ATP 40). Putting aside the status of the description one thing we can note, however, is that the discussion of abstract machines, the production of an ‘Ecumenon’, is a positive account that in many ways can complement the dissolution that is often associated with D&G. Quite commonly we come across an emphasis on ‘how to make yourself a body without organs’, which might be read as a way to ‘liberate’ oneself from having been organised behind our backs by culture or social norms or ‘ideology’, or some other mode of social construction. The discussion in this chapter, however, offers an account of “how to ‘make’ the body an organism” (ATP 41), which offers itself immediately as a compliment, almost as the other side of the coin of that process of ‘making yourself a body without organs’. As such, for those interested in how D&G or schizoanalysis might offer a route to resistance or revolution and who might be left wondering where the constructive or productive process might be discussed, this is one place to look, at how one might conceive something like the abstract machine of revolution.