Zizek, in an essay that primarily focuses on the debate between Derrida and Foucault on the subject of ‘madness’, makes some interesting comments on the nature of the limit. To quote at some length:

This brings us to the necessity of Fall: what the Kantian link between dependence and autonomy amounts to is that Fall is unavoidable, a necessary step in the moral progress of man. That is to say, in precise Kantian terms: “Fall” is the very renunciation of my radical ethical autonomy; it occurs when I take refuge in a heteronomous Law, in a Law which is experience as imposed on me from the outside, i.e., the finitude in which I search for a support to avoid the dizziness of freedom is the finitude of the external-heteronomous Law itself. Therein resides the difficulty of being a Kantian. Every parent knows that the child’s provocations, wild and “transgressive” as they may appear, ultimately conceal and express a demand, addressed at the figure of authority, to set a firm limit, to draw a line which means “This far and no further!”, thus enabling the child to achieve a clear mapping of what is possible and what is not possible. (And does the same not go also for hysteric’s provocations?) This, precisely, is what the analyst refuses to do, and this is what makes him so traumatic – paradoxically, it is the setting of a firm limit which is liberating, and it is the very absence of a firm limit which is experienced as suffocating. THIS is why the Kantian autonomy of the subject is so difficult – its implication is precisely that there is nobody outside, no external agent of “natural authority”, who can do the job for me and set me my limit, that I myself have to pose a limit to my natural “unruliness.” Although Kant famously wrote that man is an animal which needs a master, this should not deceive us: what Kant aims at is not the philosophical commonplace according to which, in contrast to animals whose behavioural patterns are grounded in their inherited instincts, man lacks such firm coordinates which, therefore, have to be imposed on him from the outside, through a cultural authority; Kant’s true aim is rather to point out how the very need of an external master is a deceptive lure: man needs a master in order to conceal from himself the deadlock of his own difficult freedom and self-responsibility. In this precise sense, a truly enlightened “mature” human being is a subject who no longer needs a master, who can fully assume the heavy burden of defining his own limitations. This basic Kantian (and also Hegelian) lesson was put very clearly by Chesterton: “Every act of will is an act of self-limitation. To desire action is to desire limitation. In that sense every act is an act of self-sacrifice.”

(Zizek; Cogito, Madness and Religion: Derrida, Foucault and then Lacan, http://www.lacan.com/zizforest.html, Lacan.com 2007; accessed 3/12/2012. The Chesterton quote is from Orthodoxy, FQ Publishing, 2004. The passage is also found in Mythology, Madness, and Laughter: Subjectivity in German Idealism; Markus Gabriel and Slavoj Zizek, Continuum 2009, p98. Emphasis added.)

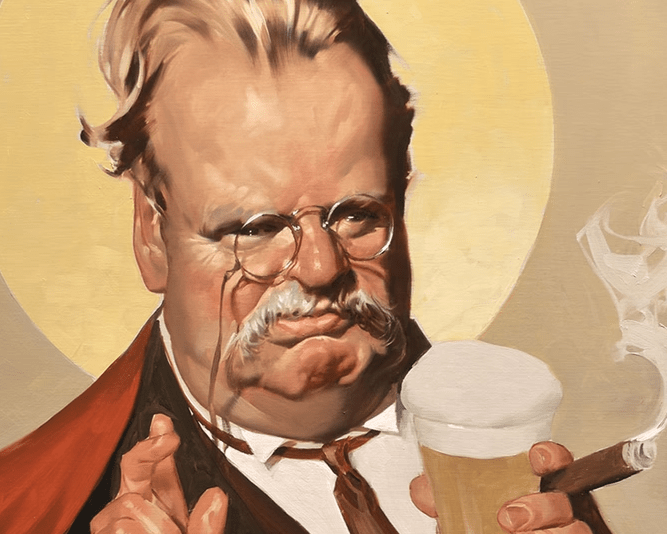

The reference to Chesterton is interesting, particularly when put back into context. Chesterton is a curious figure, not one I resonate with. For Zizek he appears as a kind of perennial coach. For my part, my distaste probably stems from the whiff of hypocrisy that attends the Catholic intellectual. The suggestion of Sainthood that was apparently once raised in relation to Chesterton only added to that bad smell. Despite this, the role of paradoxical thinking in his work is one that, elsewhere, I have found fascinating and it is no doubt this role of paradox that Zizek latches onto and that underlies that particular formula Zizek extracts. The Chestertonian formula is aimed at those, like Nietzsche, who are taken to have a general and productive or positive concept of the will. The will, for Chesterton, is negative, a privative, restrictive concept that always, by definition, limits by negating. To quote Chesterton, again at some length:

All the will-worshippers, from Nietzsche to Mr.Davidson, are really quite empty of volition. They cannot will, they can hardly wish. And if any one wants a proof of this, it can be found quite easily. It can be found in this fact: that they always talk of will as something that expands and breaks out. But it is quite the opposite. Every act of will is an act of self-limitation. To desire action is to desire limitation. In that sense every act of will is an act of self-sacrifice. When you choose anything, you reject everything else. That objection, which men of this school used to make to the act of marriage, is really an objection to every act.

(Chesterton, Orthodoxy, MobileReference edition, p35, emphasis added)

The ‘fact’ of Chesterton’s, which Zizek extracts, presenting it in the form of the formula, is clearly nothing more than an axiom, it’s presentation by Chesterton as ‘fact’ at best rhetorical. This rhetoric fits in well with Chesterton’s ‘common sense’, which is, it must be said, a curious kind of common sense, perhaps best summed up in the wonderful line that ‘fairyland is the sunny country of common sense’ (ibid, p45). Chesterton relies on a kind of convoluted common-sense, in which reason is only as reasonable as practice shows it to be. Pure reason takes you to hell. It is perhaps right to associate Chesterton’s position with Kant’s in this regard, since both argue that mature reason recognises its rationality in its practical limits. Both also limit reason in order to restore faith, Christian faith in particular. For example, later on in Orthodoxy Chesterton writes the following:

Orthodoxy makes us jump by the sudden brink of hell; it is only afterwards that we realise that this danger is the root of all drama and romance. The strongest argument for the divine grace is simply its ungraciousness. The unpopular parts of Christianity turn out when examined to be the very props of the people. The outer ring of Christianity is a rigid guard of ethical abnegations and professional priests; but inside that inhuman guard you will find the old human life dancing like children, and drinking wine like men; for Christianity is the only frame for pagan freedom. But in the modern philosophy the case is opposite; it is its outer ring that is obviously artistic and emancipated; its despair is within.

And its despair is this, that it does not really believe that there is any meaning in the universe; therefore it cannot hope to find any romance; its romances have no plots. A man cannot expect any adventures in the land of anarchy. But a man can expect any number of adventures if he goes travelling in the land of authority. One can find no meanings in a jungle of scepticism; but the man will find more and more meanings who walks through a forest of doctrine and design. Here everything has a story tied to its tail, like the tools or pictures in my father’s house; for it is my father’s house. I end where I began – at the right end. I have entered at last the gate of all good philosophy. I have come into my second childhood.

But this larger and more adventurous Christian universe has one final mark difficult to express; yet as a conclusion of the whole matter I will attempt to express it. All the real argument about religion turns on the question of whether a man who was born upside down can tell when he comes right way up. The primary paradox of Christianity is that the ordinary condition of man is not his sane or sensible condition; that the normal itself is an abnormality. That is the inmost philosophy of the Fall.

(ibid, p163 – 164)

Now it is possible to see the outlines of the position more clearly, consisting primarily in the idea that there is a need in the reasonable person for maturity, for the child to become fully a child in their second childhood. The second childhood, however, is not simply the ‘second nature’ of becoming a fully mature cultural being, it is the breakthrough to the secret of freedom produced by limitations.

My sympathies are mixed in this regard. I am profoundly anti-Christian in so far as Christianity is religious. At the same time I embrace the pagan and the magical and I am curious as to how these varying responses fit together – or whether they need to. Much of what Chesterton says regarding a ‘pure reason’ feels right, its rejection of scepticism in particular, but the framing of this rejection in terms of Christianity and limit is disturbing. Again, the sense of the ‘Fall’ and of the ‘world being upside down’ is something that spontaneously and intuitively I agree with, yet at the same time the assumption of the Fall is eschatological in the extreme, determining a need for and form of redemption through establishing the mode of beginning. I have to sort the wheat from the chaff and explore whether a coherent rejection is viable, since rejection is the response that comes to the fore when reading both Zizek and Chesterton. So where exactly might they be going wrong and where might they be going right?

Turn back to the ‘proof’ that Chesterton offers regarding the requirement of limitation in freedom. The will is not something, Chesterton argues, that ‘expands and breaks out’ but instead something that is the opposite of this, presumably therefore something that ‘contracts and contains’. Here the logical crux of Chesterton’s argument seems to be the premise that ‘when you choose anything, you reject everything else’. Putting aside, for the moment, the assumption that ‘choice’ is the form of the will, it is still not clear that to choose one thing is to deny everything else. This rests, ironically enough, on a formalism, such that ‘to choose X = to reject not-X’ (or maybe, ‘to choose X = to not-choose not-X’). It seems, perhaps, reasonable on the surface but is surely absurd. The extension of this ‘not-X’ is so indeterminate as to be worthless. It seems impossible to say, for example, that if I choose to do one thing I reject all other options. At what level do I reject these not-X’s? If I choose to brush my teeth do I somehow choose not to go to London tomorrow? The statement is wildly extreme and hyperbolic. It is clearly not the case that ‘when I choose anything I reject everything else’. Presumably this is not Chesterton’s meaning, however, so the principle of charity enables us to interpret him a little more generously. Within a restricted set of choices that are mutually exclusive then choosing one option excludes the other. This formulation, however, clearly emphasises the necessary restriction of extension implied. The problem that now appears is how did the extension become restricted? If I have 3 candidates to vote for on an election day, then the extension of the choices extends only to these three options, it would seem. We might say that given a restricted choice between A, B and C then If I vote for A I exclude, reject, both B and C. Yet even here, in the case of a ballot paper, I can choose to spoil my ballot paper. I can choose to reject the choice.

What is more likely the case is that it would seem that determinations are surrounded by a haze of indeterminations. We might say that each step on a path makes determinate a route through a maze of possible determinations but even if we try this path it is still the case that the status of these ‘possible determinations’ is not exactly obvious. Are they real in any sense at all? Are these ‘possible determinations’ perhaps the various possible worlds of Leibniz or Lewis, with the actual world surrounded on all sides by possible worlds, some of which are ‘closer’ (somehow) than others? If Caesar hadn’t crossed the Rubicon…The seemingly ‘logical’ core that is central to Chesterton’s’ argument is at best unclear and at worst incoherent.

Let’s try another of the claims, “to desire action is to desire limitation”. This seems closer to the core of Chesterton’s rejection of the productive will. Again, the question is why limitation? To desire action is to desire determination, it is to risk the dice throw that, once landed, cuts out a determinate future from the haze of possible futures. The same sort of response can surely be made about all these possible futures – what exactly are they other than some sort of formal suppositions? Is any future possible at any moment? If not, then what restricts the extension of the possible futures? Again, the problem of restriction appears and the forces of restriction – what is it that makes ‘capitalist realism’ seem so appealing, the idea, that is, that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism? Presumably the answer would refer to something that restricts our imagination, not to something that restricts the future itself – indeed isn’t that the point of the ‘capitalist realism’ idea, that somehow the future is more open than our imaginations can easily grasp at the moment?

The ‘proof’ that Chesterton offers is no such thing and I would reject it as little more than a bad formalism infecting an argument. The more informal axiom regarding the desire for action and limitation is again problematic and assumes what it needs to show. Now it might reasonably be thought that Chesterton does show, elsewhere, why any action is a limitation but it seems like that’s not in fact what happens. Instead the role of the negative is something like a metaphysical assumption. The text presents this assumption in opposition to the ‘will-worshippers’ and does so with elegance and wit. To this extent it is persuasive, providing it feels right – if your metaphysical bones resonate with the assumption then having it presented with elegance and wit is enough to persuade, or at the very least confirm assumptions. If in addition there is a collection of handy formulas provided for you to reproduce this presentation in further dialogues then all to the good, it will form the appearance of ‘enlightenment’ and clarification. It will enable the good Christian to seem both reasonable and pious, which is the aim after all. Yet it does nothing to actually engage with the will-worshippers, nothing to actually persuade anyone who doesn’t already ‘feel it’s truth’.

Now Zizek points to something a little more interesting and that we might think Chesterton is also addressing, if we were to be generous. This is found in the claim that “Kant’s true aim is rather to point out how the very need of an external master is a deceptive lure: man needs a master in order to conceal from himself the deadlock of his own difficult freedom and self-responsibility. In this precise sense, a truly enlightened “mature” human being is a subject who no longer needs a master, who can fully assume the heavy burden of defining his own limitations.” The deadlock of his own difficult freedom and self-responsibility is a curious phrase, particularly the sense of ‘deadlock’. Here we might begin to edge towards the real problem the will-worshippers present to the latent authoritarians of Zizek and Chesterton, the riskiness of the experiment and the jofulness of play.

That ‘heavy burden’ of the serious plays its crucial role for Zizek, taking the high ground against those of us who might respond with playfulness. It’s maybe this ‘seriousness’, the ominous sound of some ‘important truths that we should face up’ that really is the source of the bad smell here, a smell of the paternalism of the authoritarian who, frustrated with the children, believes that they have some kind of important truth to tell and that those children damn well ought to listen to them as they know best. It’s noticeable and telling that Zizek relies on a metaphor of authoritarian and simplistic paternalism to motivate his point here. One wonders what he could do with his model of paternalism in the face of a child who simply told him to fuck off, or who asked why he shoiuld do as he told them. I suspect the answer to any real challenge as to why they should do as they are told might too easily be, ‘because I said so’.

Leave a comment